t e m p o r a l

d o o r w a y

The Levelland Sightings Of 1957 by Antonio F. Rullán: The Ball Lightning Hypothesis

General Definition of Ball Lightning

According to James Dale Barry, author of Ball Lightning and Bead Lightning, “ball lighting is considered by many to be an atmospheric electrical phenomenon observed during thunderstorm activity. It is reported to be a single, self-contained entity that is highly luminous, mobile, globular in form, and appears to behave independently of any external force.[76]” Stanley Singer (Director of Athenex Research Associates and author of The Nature of Ball Lightning) defines ball lighting as “a luminous globe which occurs in the course of a thunderstorm. It is most often red; although varying colors including yellow, white, blue, and green have also been often reported for the glowing ball. The size varies widely, but a diameter of one-half foot is common. Its appearance is in striking contrast to ordinary lightning, for it often moves in a horizontal path near the earth at a low velocity. It may remain stationary momentarily or change course while in motion. Unlike the rapid flash of ordinary lightning, ball lightning exist for extended periods of time, several seconds or even minutes”.[77]

The Reality of Ball Lighting

On January 3, 1958, Captain Gregory (officer in charge of Blue Book) wrote a memo with his conclusion on the Levelland case. He wrote:

“After careful search, study, and consideration of all data available, the phenomenon was undoubtedly related to the meteorological condition that existed in the area at that time: fog, light rain, mist, very low ceiling (400 ft), and lightning discharges. The latter were definitely established through the result of numerous investigative reports…. In summation, all of the above were conducive to a ball lightning manifestation – a field, of which very little is known by admission of writers and authorities themselves (Dr. John Trombridge, Enclop.Am.; Prof. T.A. Blair, Univ. of Nebraska, Weather Elements, among others)”.[78]

Captain Gregory acknowledged that ball lightning was itself a controversial and unknown field back in 1957. Today, while not much has changed with regard to understanding ball lighting, there is more acceptance of its reality. According to Singer (1971):

“Despite reports of upwards of one thousand observations in the literature and more than a half dozen comprehensive, detailed reviews of the problem, including two monographs volumes, published in the last 125 years, ball lightning remains one of the greatest mysteries of thunderstorm activity.[79]”

Part of the problem of understanding ball lightning is that it has been described with a diverse and broad number of properties, which do not allow researchers to define it well. Great contradictions are found when analyzing ball lighting reports. For example, ball lightning phenomena has been reported under clear skies or under pouring rain, its color could be red, blue or any combination, it could be motionless or move very fast, it could move with the wind or against the wind, it could disappear silently or explode with a bang. Singer writes that “from the continually accumulating observations of ball lightning it gradually became clear that an unusual, if not wholly contradictory, combination of properties was indicated by the eyewitness reports. The diversity in appearance and behavior of ball lightning in different cases had led to the conclusion that different types of ball lightning may exist.”[80] Another ball lightning investigator and author tends to agree with Singer on the potential for multiple atmospheric phenomena being all lumped together under the ball lightning umbrella. According to James Dale Barry, author of Ball Lightning and Bead Lightning, “it is likely that several atmospheric electrical phenomena exist with similar but somewhat different characteristics.[81]”

Nevertheless, in a 1977 paper, Singer stated that “after a century during which several noted scientist held a negative opinion on the reality of ball lightning, it appears that in the last decade most meteorologists and perhaps a majority of physical scientists consider the existence of ball lightning well established.[82]” While ball lighting might be considered real physical phenomena, no theory has been put forward yet that can explain all the observations. While theories have been unusually numerous, no theory is accepted today amongst ball lightning researchers.

Despite the lack of a generally accepted theory to explain ball lightning and the continued discrepancy on the properties of ball lightning, we must acknowledge that an unknown atmospheric phenomenon (collectively called ball lighting) exists. Given that ball lightning is real, we must investigate whether its range of properties, behavior, and genesis describe the events in Levelland in November of 1957.

Properties of Ball Lightning

To determine what are considered general properties of ball lightning, we selected those listed by Singer and Barry in their respective books. According to Singer, “the general characteristics of ball lighting are well known. These have been obtained by study of approximately one thousand random observations by chance observers recorded over the past century and a half in the general scientific and meteorological literature.” Barry states that “the properties and characteristics of ball lightning have been deduced by a number of researchers from surveys and quasi-statistical analyses of collected reports.” Thus, the general properties listed in Table 11 are a summary of numerous reports and studies presented by earlier researchers and not just the authors’ opinion.

Table 11: Range of Properties for Ball Lightning as Documented and Catalogued by two Ball Lightning Researchers

|

Ball Lightning Properties |

Author: Stanley Singer Title: The Nature of Ball Lightning Plenum Press, NY, 1971 (Quotes are all from his book) |

Author: James D. Barry Title: Ball Lightning and Bead Lightning Plenum Press, NY, 1980 (Quotes are all from his book) |

|

Size |

The diameter of ball lightning has been reported from pea size to 12.8 meters. The average diameter has been reported as 20 cm, 25 cm, 30 cm, and 35 cm depending on which database is used. Extreme sizes of 27 m and 260 m have also been reported. The balls viewed from closer distance are usually associated with smaller diameters; the larger dimensions have been reported for distant sightings in which the estimation of the size is dependent on the distance of the object, which could itself only be approximated. |

Dimensions of the spherical or oval-shaped ball lightning vary from a few centimeters to several meters in diameter. The most common diameter reported is 10-40 cm. A spherical or oval shape with a diameter less than about 40-cm is most frequently reported. |

|

Shape (protrusions, rays, halos, or corona) |

Generally spherical or ball shaped in 83% in Brand’s database and in 87% of cases in Rayle’s database. A few oval or egg-shaped masses have also been observed. |

Ball lightning has been reported with spherical, oval, teardrop, and even rod shapes. There are three structural types. First, a solid appearance with a dull or reflecting surface or a solid core within a translucent envelope; second, a rotating structure, suggestive of internal motion and stress; and third, a structure with a burning appearance. The burning structure has been reported most often with the spherical and oval shapes, a red or red-yellow color, and a diameter less than 40 cm. |

|

Structure |

Ball lightning reported to have a solid structure commonly has a green or violet color and a diameter between 30 and 50 cm. The rotating structure is observed with a combination of colors. It usually has a bright-colored interior with darker colored poles or a translucent envelope. |

|

|

Color |

Red and orange colors are reported most frequently for ball lighting according to the five major surveys. Red was by far the most common color. Yellow, white, blue and blue-white are also commonly reported. Barry found less than 2% were blue or blue white in his study. Green is noted relatively rarely. |

Most ball lightning reports indicate the object as having had a red, re-yellow, or yellow color. Other colors, including white, green and purple were occasionally reported. Blue and blue-white colors are associated with reports of St. Elmo’s fire. A color change with time was reported by only a few of the observers. These changes fall into three categories: red to white, violet to white, and yellow to white. |

|

Duration |

Most common lifetime is from 1 to 5 seconds. An appreciable number disappear in less than a second and the examples with a lifetime longer than 5 seconds are markedly fewer. Several exhibit a lifetime of the order of 1 minute, and individual observations for 9 minutes and 15 minutes have been recorded. The longer lifetimes, extending to periods of a minute, were correlated with motionless blue or blue-white globes in the survey by Barry, who concluded that such globes were actually St. Elmo’s fire. |

The lifetime of a ball lightning is most often reported to be only 1-2 seconds. A lifetime of this length or less was reported or indicated in about 80% of the reports examined. A small percentage of reports indicated longer lifetimes, lasting up to minutes. The longer lifetime is highly correlated with the motionless blue or blue-white ball, which is considered to be St. Elmo’s Fire. |

|

Evidence of Heat |

The absence of any heat radiating from ball lighting has been especially noted as unusual for a body emitting such intense light. This property is reported in by far the larger number of cases. Brand concluded that, in general, no heat effect is exhibited by ball lightning of the type which floats free in the air. |

A small number of observers reported that heat emission was experienced during the event. Death attributed to ball lightning has also been reported. Damage to objects that were touched by a ball lightning has also been reported. In contrast to these reports of serious damage, others have indicated that ball lightning does not emit heat and does not cause harm to objects. |

|

Motion (velocity, path, rotation, direction with respect to wind) |

Two categories of motion have been distinguished; the luminous globes which fall to earth from the upper atmosphere and those which travel near the ground and are formed following a lightning stoke to earth. The general paths which have been observed include direct descend from the clouds to the ground, horizontal flight close to the earth with the wind or sometimes directly against the wind, upward flight, up and down motion, or rebounding from the earth. Velocities range from 1 meter/sec to 240 meters/second. |

In general, ball lightning is most commonly observed in descending motion apparently from a cloud. It usually assumes either a random or horizontal motion several meters above the ground. The motionless state often results after an initial random or horizontal motion, although it can occur sooner. Cloud-to-cloud motion and earth-to-cloud motion are reported least - only a few of over 1600 reports indicate such motion. The motionless ball lightning is observed to hover in midair, seemingly unaffected by external forces. It is usually red or yellow white in color, spherical or oval shaped with a diameter of about 30-cm. It is often observed to undergo a sudden attraction to a grounded object. It darts quickly to the grounded object and decays noisily upon contact. The data accumulated indicate that if a wind-related motion is mentioned in a report, the ball lightning is most often observed to move along with the wind rather than against it. |

|

Smell |

Smells described as being of sulfur and ozone are common. In a few cases the odor was compared with that of nitrogen dioxide. General odors of burning have also been reported. Approximately one-quarter of the globes reported in Rayle’s survey were associated with a smell. |

Many observers report a distinctive odor accompanying the presence of ball lightning. The odor is described as sharp and repugnant, resembling ozone, burning sulfur, or nitric oxide. The odor is reported most often when the distance between the ball lightning and the observer is small. Odors of this type are common ionization products of a lightning discharge. |

|

Sound |

Various sounds are emitted by ball lightning. The most common sound reported is a hissing or crackling noise. In some observations ball lightning is reported as entirely silent. |

A characteristic hissing sound is often associated with the presence of ball lightning by many review authors. Only a few first-person reports were found which specifically mentioned a sound characteristic in connection with a nearby ball lightning observation. Conversely, a hissing sound is definitely associated with the St. Elmo’s fire phenomenon which is occasionally misidentified as ball lightning. Consequently, we may conclude that ball lightning is predominantly a soundless phenomenon. |

|

Emission of sparks or lightning from the ball |

Emission of sparks or long fiery rays from ball lightning has been noted in several occurrences giving rise to a frequent description of the luminous mass as a firework. |

|

|

Disappearance of the ball (Explosive or Silent) |

The disappearance of ball lightning often occurs silently, but in many cases there is a violent explosion. Barry’s survey indicated that a majority exploded, including 80% of the red balls and 90% of the yellow. |

Ball lightning has been observed to decays by two modes. One is the silent decay, associated with a decrease in brightness and diameter. The second, designated as the explosive mode, is associated with a loud violent sound. Some observers report a sudden color change preceding the explosive decay. |

|

Traces left by the ball (Burns, damage, etc.) |

In many ball lightning occurrences no permanent traces are found after disappearance of the ball despite its awesome activity. |

A small percentage of observers mentioned a residue found after the decay. These include, smoke or god residue and a tar or soot residue. |

|

Change in appearance of the ball (change is size or color) |

No change in the appearance of ball lightning is noted during its existence for by far the larger number of cases, but in a small number definite changes have been observed in the size, shape or color. Changes in size may involve either a decrease or an increase. The light intensity of 12 cases in Rayle diminished and two increased. Color changes have also been specifically considered by Brad and Mathias. |

Barry found less than 1% of the observation in his survey of the literature indicated a change in color, and all of these involved a change to bright or dazzling white of balls from the initial red, violet, or yellow colors. |

|

Time of day of the occurrence |

The greatest frequency of appearance of the balls came approximately two hours later than the peak in storms during the day but otherwise roughly resembled the distribution with time of day exhibited by storms. The fiery globes were most numerous in the summer months, 63% of the cases considered by Brand according to this parameter coming in this season and a total of 80% from May through September, again closely following the yearly distribution of storms. The data of Rayle’s collection dealing largely with observations in the central United States also show the greatest number appearing in summer, 83%. The frequency of ball lightning is thus evidently associated with the frequency of thunderstorms. |

|

|

Occurrence during storm and connection with flashes of linear lightning |

The number of ball lightning appearances not directly connected with a storm is very small. Barry estimated that 90% of the cases reported occurred during thunderstorm activity. In three incidents for which reasonable complete accounts are available there appears the possibility of some distant residue of storm activity although the ball appeared under sunny skies which were clear or contained, at most, a few clouds. Of the reports gathered by McNally, three indicated the formation of ball lightning under a clear sky, and Rayle reported five which did not occur in a storm. The majority of ball lightning incidents are further specifically associated with discharges of ordinary lightning, which may appear either before or after the ball lightning. |

The occurrence of ball lightning is commonly associated with natural lightning events during thunderstorms, tornadoes, earthquakes, and other such stressful conditions in natures. These observations are the basis for the assumption that ball lightning is associated with the ordinary lightning discharge and is an electrical phenomenon. This association is supported by reports that describe a ball lightning appearing simultaneously with a nearby ordinary lightning discharge, immediately following the storm or just preceding the discharge. About 90% of the ball lightning observations reported occurred during thunderstorm activity. |

Deviations between Levelland Sighting Descriptions and Ball Lightning Properties

One way of evaluating whether the ball lighting hypothesis explains the phenomena observed in Levelland is to compare the descriptions given by the seven witnesses to the ranges of properties observed in ball lightning. If all the descriptions of the objects seen in Levelland fall within the ranges of ball lightning properties summarized by Singer and Barry, then it is reasonable to assume that the observed phenomena was ball lightning. On the other hand, if we observe significant deviations from observed ball lightning properties, then the ball lightning hypothesis must be rejected.

Table 12 summarizes the key deviations between the descriptions of the seven Levelland sightings and the ranges for 13 ball lightning properties. The key interest here is in deviation from the observed ranges given by Singer and Barry. If the Levelland sighting description does not meet the average property of ball lighting but is within range, then it could be classified as ball lighting. If a property was not reported by the witness, then we can not judge it and we identify it as Not Available.

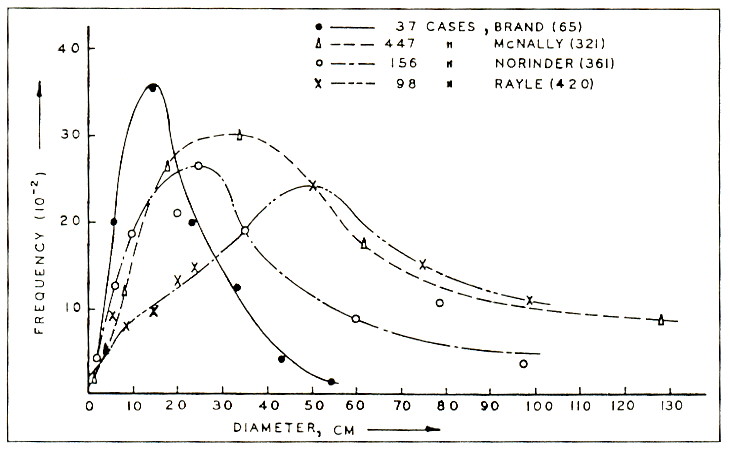

The reported size of the Levelland object was a key deviant from size ranges given to ball lighting. While Singer states that the largest size of ball lighting observed was 12.8 meters (or about 41 ft), Saucedo, Wheeler, and Long stated that the object seen was about 200 ft. Two hundred feet is way beyond the upper bound given by Singer. Singer created a graph of the frequency distribution of ball lightning diameters for four databases of ball lightning observations covering about 738 observations. In this graph, shown in Figure 8, Singer shows that the largest diameter on these databases was only about 4.2 ft. Thus, either the witnesses overestimated the size of the object seen, a new record size ball lighting was discovered, or the observed object was not ball lightning. The other witnesses who gave size estimates said that the ball of light was a wide as the road. A two-lane road is less than 30 ft wide; thus these other descriptions fit the range of observed ball lightning sizes.

Figure 8: Distribution of Ball Lightning Diameters[83]

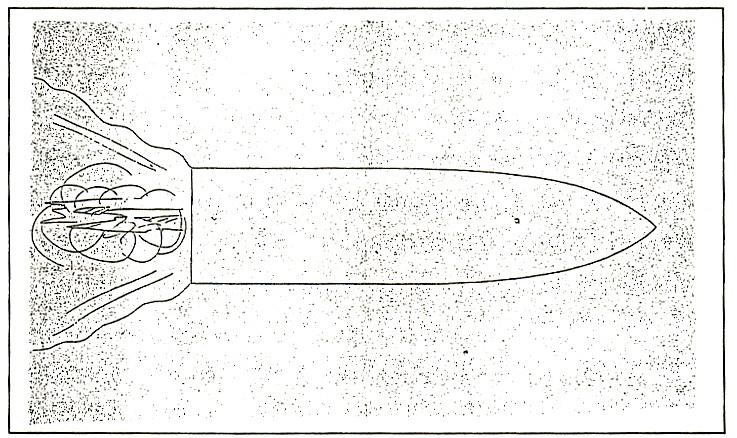

Shape descriptions for ball lightning matched all Levelland descriptions. While Saucedo’s description of a torpedo or rocket shaped object is rare in ball lightning reports, Barry states that rod shaped ball lighting has been reported. Classifying Saucedo’s drawing of his sighting (made for the Air Force investigator and shown in Figure 9 below) as rod-shaped ball lighting might be considered unlikely but not impossible. For example, Corliss (in his book Handbook of Unusual Natural Phenomena) discusses the sighting of a rod-shaped ball lightning that was described by the witness as torpedo shaped.[84]

Figure 9: Pedro Saucedo’s Drawing of His Sighting[85]

All colors reported by the Levelland witnesses were within range of those reported in ball lightning observations. A few witnesses described the light as a neon sign but no color was given. Even if we assume that the witness saw the typical color of neon gas (orange-red), it is still within the range of colors in ball lightning descriptions.

Only three witnesses gave duration of observations, ranging from 2 minutes to 15 minutes. Eyewitness estimates of time are usually not very reliable, especially during a stressful event. In the Levelland case, for example, Mr. Newell Wright was recently asked about his report stating that his sighting lasted 4 minutes, and he replied that it probably lasted seconds but felt like minutes. Despite the unreliability of eyewitness time measurements, the reported times are within the ranges given by Singer and Barry. While Singer and Barry say that the most common ball lightning lifetimes are 1 to 5 seconds, they do report sightings lasting minutes. Thus, duration of the Levelland sightings does not rule out ball lightning.

The motions observed in ball lightning are usually horizontal and vertical, which fit the descriptions of all Levelland eyewitnesses except Alvarez’s. Most of the witnesses reported the ball of light departing vertically upward which is rare in ball lightning reports. According to Barry, earth-to-cloud motions are reported least (only a few of over 1600 reports indicate such motion). Nevertheless, however uncommon, ball lighting reports with upward motion have been recorded according to Singer and Barry. Thus, the majority of the observed motions in the Levelland sightings fall within the range of motions in ball lightning. The Alvarez sighting, however, describes the object as circling a cotton field just above the ground. This type of motion was not found in Singer and Barry’s descriptions of ball lightning motion. Barry does mention that spiral motions have been reported, but a spiraling motion is not the same as a circling motion. Thus, Alvarez description of motion is considered a deviation from the ranges given to ball lightning motion.

Smell is an interesting ball lightning property because none of the Levelland witnesses reported smelling anything. Singer and Barry, however, say that not all ball lightning observers report smell. According to Barry, witnesses who are closer to the ball of light report smells more often. Nevertheless, either witnesses did not smell anything or maybe they said it but nobody wrote it down. No conclusion for or against the ball lightning hypotheses can be made based on the lack of smells reported.

Sound is another ball lightning property that does not help distinguish between ball lightning and something else. According to Singer and Barry, ball lightning has been reported with and without sound. Barry, however, states that ball lightning is a predominantly soundless phenomenon. Of the seven Levelland witnesses, four reported no sound. The three that did report sound described it as thunder. Saucedo appears to have heard the sound as the object passed over his truck, Williams heard the sound when the object took off vertically, and Long heard the sound when it settled to the ground and again as it took off. These sounds tend to agree more with what Singer and Barry describe as the explosive mode of disappearance of ball lighting. Apparently, ball lightning has been reported to disappear either silently or with a loud violent sound. Either way, all seven Levelland sighting reports fall within this range of ball lighting disappearance.

No traces were left by any of the Levelland sightings, which matches the majority of ball lightning observations. Some ball lightning reports emit sparks or long fiery rays. Thus, Saucedo description of a blue object with a yellow flame coming out of the rear could fall within the ball lighting emissions described by Singer.

With regard to changes in color or light intensity, a small number of ball lightning reports have observed changes in size, shape, intensity, and color. In the Levelland cases, Ronald Martin, James Long, and Frank Williams reported changes in appearance. Martin reported color changes from orange to bluish-green and back to orange. Long and Williams reported that the object’s light was blinking on and off like a neon sign. Barry found that less than 1% of the observations in his survey indicated a change in color. Nevertheless, all of these involved a change from red, violet, or yellow to white. While Barry’s color changes are different than Martin’s reported color changes, the key point is that color changes have been reported in ball lightning observations and thus Martin’s description is not a significant deviation. Long’s and William’s observation, on the other hand, has not been reported in connection to ball lightning. Singer writes that 14 ball lightning cases have been reported with changes in light intensity (in 12 of these the light intensity increase and in 2 it decreased). Nevertheless, light intensity changes are not the same as a pulsating light. Thus, we consider Long and William’s observations as deviant from the ball lightning observations on changes in appearance.

The occurrence of ball lighting during storms or connected with linear lightning is very important to the Levelland case because many previous investigators discounted the hypotheses when no evidence of a lightning storm was found in Levelland. Dr. James McDonald, who did not agree with the ball lightning hypotheses, wrote: “if there are any workers in atmospheric electricity who hold that ball lightning can be generated without presence of intensely active thunderstorms, I have failed to uncover such viewpoints in a recent extensive review that I carried out on the ball lightning problem.[86]”

Singer and Barry tend to agree with Dr. McDonald in that the majority of the ball lightning cases have been reported in connection with a lightning storm. Nevertheless, according to Barry, 10% of the reported ball lightning cases have occurred without thunderstorm activity. A few of these reported cases have occurred under sunny skies, which were clear or contained a few clouds. While a lightning storm might not be required, the majority of ball lightning incidents are specifically associated with ordinary lightning discharges that may appear either before or after the ball lighting. Singer refers to McNally’s and Rayle’s collection of cases (447 and 98 respectively) in which 85% and 70% of the ball lighting cases were seen in conjunction with ordinary lightning flashes. Based on these observations, we must not discount ball lightning as a potential cause of the Levelland sightings just because no lightning storm was present. As unlikely as it seems, weather conditions during the time of the Levelland sightings do not preclude ball lightning.

Table 12: Deviations between Levelland Sightings Descriptions and the Properties of Ball Lighting

|

Ball Lightning Properties |

Pedro Saucedo |

Jim Wheeler |

Jose Alvarez |

Newell Wright |

Frank Williams |

Ronald Martin |

James Long |

|

Size |

x | x |

NA |

t |

NA |

t | x |

|

Shape (protrusions, rays, halos, corona) |

t | t | t | t | t | t | t |

|

Color |

t | t |

NA |

t |

NA |

t |

NA |

|

Duration |

t |

NA |

NA |

t |

NA |

t |

NA |

|

Evidence of Heat |

t |

NA |

NA |

t |

NA |

t | t |

|

Motion (Horizontal, Vertical) |

t | t | x | t | t | t | t |

|

Smell |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|

Sound |

t | t | t | t | t | t | t |

|

Emission of sparks or lightning from the ball |

t |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

|

Disappearance of the ball (Explosive or Silent) |

t | t | t | t | t | t | t |

|

Traces left by the ball (Burns, damage,etc.) |

t | t | t | t | t | t | t |

|

Change in appearance of the ball (size or color) |

t | t | t | t | x | t | x |

|

Occurrence during storm and connection with linear lightning |

t |

NA |

NA |

t |

NA |

NA |

NA |

t (green) = Within Range of Singer and Barry’s Ball lightning Descriptions

x (red) = Not Within Range given by Singer and Barry

N (yellow) = Not Observed

NA = No Data Available or Not Reported

Fitness of Ball Lightning Hypotheses

The ball lightning hypotheses was proposed by the Air Force to explain all the facts observed in Newell Wright’s Levelland sighting. The Air Force did not consider Saucedo’s sighting worthy of explanation because they attributed it to imagination. Since then, however, the ball lightning hypothesis has been used to explain all of the Levelland sightings that caused vehicle interference. The ball lightning hypothesis must explain all of the reported observations for it to be accepted. Detail analysis of the witness testimony and comparisons between descriptions of the Levelland sightings and the properties of ball lighting (as documented by Singer and Barry) indicate that there are some discrepancies. This section will discuss the discrepancies and issues that prevent the full acceptance of the ball lightning hypothesis. There are four key issues that are relevant to the acceptance or rejection of the ball lightning hypothesis: (1) weather (2) deviations from ball lighting properties (3) effect on automobile ignition and (4) other anomalous effects observed.

Ball lightning has been rejected as an explanation for the Levelland sightings because it was assumed that its presence required a lightning storm. Because there was no lightning storm in Levelland on the night of November 2 1957, it was concluded that ball lightning could not have been generated. Contrary to popular belief, Singer and Barry report that about 10% of the ball lightning cases occur without the presence of a lightning storm. Singer points out, however, that sometimes ball lighting is seen in conjunction with a few lightning flashes but no storm. Nevertheless, clear sky ball lighting has been observed. Thus, the ball lightning hypothesis cannot be rejected purely because no lightning storm was present.

While no lightning storm was present in Levelland, weather conditions conducive to lightning did exist. Based on weather reports from Lubbock, lightning was reported in the area one hour after the sightings. Thunder and lighting were reported in Lubbock between 2 AM and 3 AM on November 3. Moreover, weather reports from Levelland indicate that thunderstorms were reported in Levelland on November 3. While these weather reports are not proof that lightning conditions existed in Levelland at the time of the sightings, they do reject the idea that weather conditions in the area were not conducive to lightning formation. The combination of these two facts (1) the possibility of ball lightning formation without lightning storms and (2) the observation of lightning in Lubbock one hour after the incidents prevent us from rejecting the ball lightning hypothesis for reasons of weather.

The comparison of the Levelland sighting descriptions to the observed properties of ball lightning led to some discrepancies that must be addressed to either reject or accept the ball lightning hypothesis. There were three areas where the Levelland descriptions did not match the ball lightning properties (as catalogued by Singer and Barry). These areas of discrepancy were (1) size (2) motion and (3) change in appearance. The size given by Saucedo, Wheeler and Long (200 ft) is beyond the size of any observed ball lightning. The largest reported size being about 41 ft. Such a deviation in size leads us to conclude that either the three witnesses misjudged the size, a new record size of ball lightning was discovered, or the object was not ball lightning. Eyewitnesses are typically not good measuring instruments for sizing a bright object at a distance at night. For example, Newell Wright originally stated on his Air Force interview that the object’s size was between 75 and 125 ft. However, when questioned 42 years later, he said that the object was not wider than the road. Thus, size discrepancy should not be the only basis for rejecting the ball lightning hypotheses.

A more significant deviation between the Levelland sighting descriptions and ball lighting properties is the change in appearance reported by Long and Williams. Both of them reported that the object was blinking on and off like a neon light. This description does not match any ball lighting report in Singer and Barry’s books. Thus, the observed blinking was either a very rare ball lightning property (that has not been reported) or it was the property of some other unknown object or phenomena.

Another deviation between the Levelland sightings and the observed properties of ball lighting was the motion of the object observed by Jose Alvarez. He described the object as moving in circles above a cotton field. A circling motion is not within the range of observed motions for ball lightning as described by Singer and Barry. Thus, this observed motion is either a rare case of ball lightning motion or it was the property of some other unknown object or phenomena.

The most common and controversial reason for rejecting the ball lightning hypothesis is the reported shutdown of the automobile engines and headlights by the Levelland object subsequently followed by their normal startup when the object left. In the extensive summary of cases provided by Singer (1971) and Barry (1980), no mention was made of ball lightning effects on automobiles. The effect of ball lightning stopping automobile engines was not reported in their summaries of traces left, damage, and heat. The few cases where ball lightning did cause damage, the effect ranged from dust raised by the ball, burns in material which the ball has touched, holes bored in walls, to the collapse of a building caused by the explosion of the fireball. While a few cases have been reported of ball lightning interacting with airplanes and entering houses, these cases offer no help in understanding the effects on automobiles.

A search of the bibliography of ball lightning did not uncover any papers on the effect of ball lightning on automobiles. Dr. Peter H. Handel (professor at the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Missouri and a theorist on ball lighting formation) replied to the author’s inquiry on this subject stating that “there are no papers specifically written on the interaction of ball lightning with cars and appliances.” Thus, it appears that the scientists and investigators who study the ball lightning phenomena are not making the claim (based on case studies) that ball lightning has stopped automobile engines from afar.

Dr. Martin D. Altschuler, author of the chapter titled “Atmospheric Electricity and Plasma Interpretations of UFOs” in the Condon Report and a member of the Astrophysics Department at the University of Colorado in 1968, purposely omitted the discussion of the feasibility of ball lightning interfering with automobiles[87]. The two reasons he gave for omitting the discussion were (1) that there was no connection between the observed unknown object and the vehicle interference and (2) that no unusual magnetic patterns have so far been found in auto bodies (despite the fact that the Condon Study only evaluated one vehicle). Nevertheless, he does address the plasma hypotheses that was proposed by Phillip Klass (in his book UFOs Identified) to explain vehicle interference. Dr. Altschuler writes that “it is difficult to explain how a UFO-plasma could gain entry to the car battery in the engine compartment without first dissipating its energy to the metal body of the car.”[88]

In this study we have assumed a direct connection between the Levelland object and vehicle interference. This assumption is not deemed unreasonable because of the number of similar cases reported in Levelland within a period of only 2.5 hours. If only one witness had reported this incident, then maybe we could have rationalized it as two independent events. But when seven witnesses report the presence of a brilliant object in conjunction with their vehicles shutting down, then the probability of these two events being dependent becomes significant.

The Air Force also concluded that there was a linkage between the ball of light and the vehicle interference. The Air Force explanation, however, is not fully supported by the scientific community. The claim that “the high humidity may have resulted in sudden deposition of moisture on distributor parts and the possibility of stoppage due to this is especially true if moisture condensation nuclei were enhanced by increased atmospheric ionization”[89] has not been proven. McCampbell (1975) has also suggested that ionization of atmospheric gases might lead to the vehicle shutdown followed by restart when the object leaves[90]. But instead of suggesting that the object causing this effect is ball lightning, McCampbell suggests that the object is a craft whose propulsion system ionizes the air. Nevertheless, if experimentation shows that ionization of moist air around a 1957 type vehicle leads to engine shutdown, then it would be more likely to support the ball lightning hypothesis than some other.

There were also three anomalous observations reported in Levelland that defy the ball lightning hypothesis. These observations were reported by four of the seven Levelland witnesses (Pedro Saucedo, James Long, Jim Wheeler, and Frank Williams). James Long reported seeing an object with its light off in the middle of the road ahead of him, and when he approached it in his truck, the object’s light turned on. This description, obviously, does not fit the definition or any description of ball lightning. To support the ball lightning hypotheses requires us to discount this story as misinterpretation by the witness or bad reporting. James Long’s story was documented second hand to the press. Only A.J. Fowler talked to Long. George Dolan, one of the few journalists who interviewed Fowler, is the only reporter who wrote this claim in a newspaper. Thus, we must accept this claim with caution and doubt.

Another anomalous observation was the timing of the departure of the brilliant object. Wheeler, Williams, and Long reported that as they got out of their cars/trucks in order to approach the light, it took off straight up and disappeared. It is odd that in three of the five Levelland cases were the object was sitting/hovering on the road, the object left at the moment when the witnesses tried to approach it on foot. This type of behavior is more likely to denote intelligence than the fact that five of the seven sightings took place in the middle of the road (as suggested by James A. Lee). Nevertheless, the timing of the object’s exit might just be a coincidental result from ball lightning that does imply intelligence. Moreover, the quality of the reports obtained from these three witnesses was previously determined to be low and these claims should be weighted appropriately. Overall, the timing of the object’s exit is not conclusive evidence for rejecting the ball lightning hypothesis.

The third observation came from Pedro Saucedo and was well documented by the Air Force and the press. He stated that the object caused a rush of wind that rocked his truck. This type of physical force was not found in the ball lightning literature as an observed property of ball lightning. Thus, what Saucedo experienced does not fit the description of ball lightning effects. Because Saucedo’s claim is deemed accurate and cannot be discounted, we must either reject the ball lightning hypothesis as the cause of his sighting or look more thoroughly for evidence that fast moving ball lightning can cause a rush of wind that can rock a truck.

In conclusion, we reject the ball lightning hypotheses mainly because of lack of evidence that ball lightning causes vehicle interference and not because of the lack of a storm during the sightings. Other reasons for rejecting the ball lightning hypothesis, however, are more contingent on the accuracy of the details given on eyewitness testimony. A summary of the other evidence that could be used to reject the ball lightning hypothesis is shown below in Table 13. The table splits the claims between those witness reports whose accuracy was deemed High/Medium and those reports whose accuracy was deemed Low.

Table 13: Summary of Witness Observations that Do Not Fit the Ball Lightning Hypotheses

|

Reported Observations that are not within the Range of Ball Lightning Properties |

Reported by Witnesses whose Report’s Accuracy was Deemed High/Medium |

Reported by Witnesses whose Report’s Accuracy was Deemed Low |

|

Size of object was ~ 200 ft |

1 |

2 |

|

Object was blinking on and off like a neon light |

None |

2 |

|

Object was moving in circles |

None |

1 |

|

Object had its light off in the middle of the road |

None |

1 |

|

Object departed when witnessed got out of vehicle & approached it |

None |

3 |

|

Object caused a rush of wind that rocked a truck |

1 |

None |

Table 13 shows that most of the deviant observations (observations that could be used to reject the ball lightning hypotheses) were made by witnesses whose reports are considered low in accuracy. If we had to judge the Levelland sightings by only using reports of High/Medium accuracy (Saucedo, Wright, and Martin), and assume that Saucedo misjudged the size of the object, then these three observations would fall within ball lightning parameters with the exception of the vehicle interference and wind effects.

The claim that ball lightning cannot momentarily stop engines and turn off headlights is still an area that needs further research and is not a foregone conclusion. If in the future, ball lighting researchers find conclusive evidence that ball lighting could interfere with vehicles in the same fashion as Levelland, then we must conclude that the ball lightning hypothesis explains the three Levelland reports of High/Medium accuracy. Moreover, if the three reports with the most accurate details could be explained by the ball lightning hypotheses, then it is very likely that ball lighting also caused the other four reports (whose details were of low accuracy). This conjecture, however, requires us to discount the testimony from 4 eyewitnesses. This might not be unreasonable given that these witnesses were never interviewed and their claims were not fully documented.

Other evidence in support of the ball lightning hypotheses is that all seven reports gave different descriptions for the observed object. The variety of descriptions (shape, size, and color) for the light source implies that the same object was not seen seven times in 2.5 hours. Either there was more than one object seen that evening or it was a phenomenon whose properties were variable and diverse like ball lightning.

Despite these observations that support the ball lightning hypothesis, we must reject it as the explanation of the Levelland sightings because of the lack of evidence for it causing vehicle interference. Thus, we conclude that the cause for Levelland sightings continue to remain Unknown.